by Louis Cinquino

Fill in the blank: _______ is a state of performance where a person becomes totally absorbed in and engaged by an activity.

If you happen to be Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, renowned psychologist and author of Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, you no doubt used the title of your book to fill in the blank.

If you are a WholeRunner, you may have a different answer: the Runners’ High.

According to Csikszentmihalyi, flow is often associated with a work environment, where, among other conditions, there is a healthy tension between working on a challenging assignment and an emerging set of our skills that we have confidence in. We are pushed, yet we have what we need to succeed.

Yet it’s not only commercial work that brings us into this blissful territory of performance. It’s also sport. And where’s there’s sport, there are people trying to engineer victory.

Flow for Athletes vs. the Rest of Us

Seeing this state of mind as providing a possible competitive edge, sports psychologists have sought to engineer the experience of flow for athletes. However, in Flow in Sports, Csikszentmihalyi and coauthor Susan Jackson explain that while flow is always a peak, satisfying experience, it is not necessarily associated with peak performance on every occasion.

This is important for us to realize: Flow is not necessarily going to lead to your fastest time in and of itself. However, flow will absolutely maximize the enjoyment and richness of your run in a way that can clearly lead to performance.

A supporting paper, coauthored by Jackson, along with Jay Kimiecik and Herb March, and published in the Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, clarified the elements that were most present in athletes where flow was registered. The study of master athletes found that the most powerful correlations to the flow experience were to “a high perception of sport ability” and “intrinsic motivation … when someone engages in an activity because of the pleasurable and exciting feelings associated with the movement of the activity itself.”

Athletes who experienced this peak feeling believed that they were prepared, and loved what they were doing. In other words, they had gained a level of skill that they perceived to be sufficient for the challenges they faced, and they held an appreciation for the activity they were performing.

The paper also references earlier findings that being pushed to a higher challenge correlates with quality of experience only in a recreational sample, not in a competitiveone. Perhaps, for truly competitive athletes, being pushed to higher levels is just part of their routine. For recreational athletes, that combination of preparedness and aspiration is perhaps more rare, so when it happens, it can ignite a much higher-quality—i.e., flow—experience.

In other words, flow is not for the Olympians. Flow is for us. Flow is something that we, as recreational yet engaged runners, are uniquely positioned to experience.

What’s Flow Really About?

Flow isn’t about being the fastest runner—it’s about being a WholeRunner.

Flow is about feeling better and running happier, more mindfully, more ecstatically—it is the mythical runner’s high that was once as ubiquitous and contentious a topic of debate as the existence of Sasquatch or Chariot of the Gods. Now we know that our Bigfoot is real.

So how do we have flow experiences more often when we run?

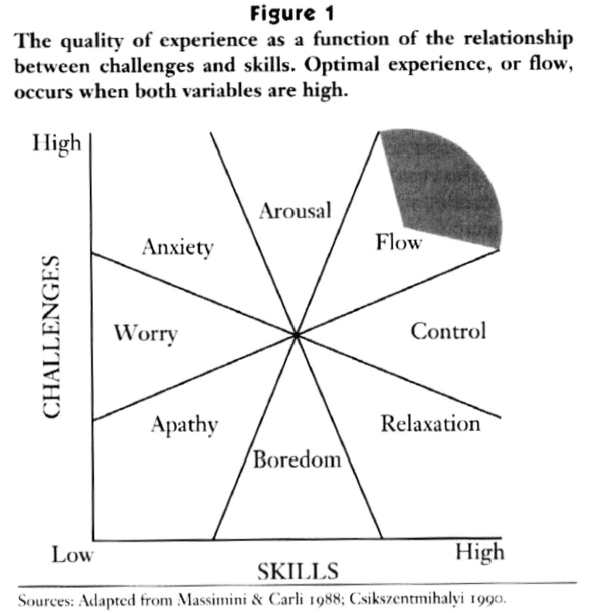

It took me a bit of time to really understand this chart I found on Alex Vermeer’s notes from Csikzentmihalyi’s Finding Flow, but it was worth it.

The flow experience in the upper right of the chart is where our challenges are perceived to be high, but so is our perceived skill level. Flow sits between arousal (being engaged by a challenge, bordering on anxiety about an outcome) and control (knowing exactly what the outcome will be, bordering on relaxation and ease). There’s no worry (because we know we are prepared) and no boredom (because we know we are being actively challenged). It is the opposite of apathy (where nothing is interesting or demanding).

Csikszentmihalyi himself characterizes flow as an almost ecstatic state, when time seems to disappear and you lose yourself in the feeling of being something larger. It’s as close to a scientific definition of runner’s high that I’ve ever found.

Running not only provides flow experiences, it can also help us understand the nine distinct elements of flow, all of which can occur regularly with our running. We are not just training for a race, we are training ourselves to experience flow in other aspects of our lives when we directly experience these elements in our running.

The Nine Elements of Flow in WholeRunning

- 1. Challenge-skills balance: We believe that we are prepared to run a specific race or route, but know it won’t be easy.

- 2. Action-awareness merging: We run and we know we are running. We pay attention to it, rather than trying to disassociate with our running by escaping from it into our headphones.

- 3. Clear goals: We state in advance how long or how far or how fast we want to run, and move consciously toward that goal.

- 4. Unambiguous feedback: We either hit our goal or we don’t. We either feel too exhausted to climb that hill, or we rise to the task and make it. The clock is ticking.

- 5. Concentration on the task at hand: We spend our time running and appreciating what we are doing, rather than letting our mind obsess on other challenges or setbacks in our life.

- 6. Sense of control: We are the ones lacing up our shoes and doing this or not doing it. There’s no one else to blame.

- 7. Loss of self-consciousness: We become part of the landscape without feeling that we are intruding into other people’s space or that they are judging us. We belong in this race. We may sweaty and tired, but we don’t let that bother us.

- 8. Transformation of time: We take off the watch or turn it around so we can run and let the time be what it is. Time is no longer important—our bodies become our feedback.

- 9. Autotelic (intrinsically rewarding) experience: We consider the joys of moving freely, passing through the air, the physical sensations of being strong and healthy enough to engage in such a physically demanding sport. We are not preparing for some future payback—we are merely being the way we want to be.

Running, when it’s done with these nine elements of flow, is an incredible gift to our whole person. It’s like a short cut to the direct and repeatable experience of flow. This approach, which I call Running the Whole Way, does so much more than train us to be better runners. Through the flow of the runner’s high, this visceral experience brings awareness to how we can generate peak experiences in other aspects of our lives.

Read more blog posts in Louis Cinquino’s WholeRunner series.

Louis Cinquino is a writer, Certified Distance Running Coach, life coach, dad, and graduate of CiPP4 and Positive Psychology Coaching Fundamentals. His personal observations, discoveries, and training plan as he prepared for the Fifth Avenue Mile race were featured in “The Mulligan Mile,” (Runners World, September 2013). He is currently developing WholeRunner: Your Inside Track to Happiness, a project to explore and explain the positive psychology of running. You can read more from Louis on his blog, TakingMulligans.com.

Louis Cinquino is a writer, Certified Distance Running Coach, life coach, dad, and graduate of CiPP4 and Positive Psychology Coaching Fundamentals. His personal observations, discoveries, and training plan as he prepared for the Fifth Avenue Mile race were featured in “The Mulligan Mile,” (Runners World, September 2013). He is currently developing WholeRunner: Your Inside Track to Happiness, a project to explore and explain the positive psychology of running. You can read more from Louis on his blog,

Louis Cinquino is a writer, Certified Distance Running Coach, life coach, dad, and graduate of CiPP4 and Positive Psychology Coaching Fundamentals. His personal observations, discoveries, and training plan as he prepared for the Fifth Avenue Mile race were featured in “The Mulligan Mile,” (Runners World, September 2013). He is currently developing WholeRunner: Your Inside Track to Happiness, a project to explore and explain the positive psychology of running. You can read more from Louis on his blog,

This is article Can I contact you? Can I write to you directly. It’s so good that i’m going follow you!

Yes, please do! My contact info is on my blog, TakingMulligans.com