by Warren Goldstein-Gelb

For my 50th birthday, I decided to treat myself by enrolling in WBI’s Certificate in Positive Psychology (CiPP) program at Kripalu. I wanted to figure out how to spend the second half of my life.

Three years later, I awoke after being unconscious for nearly a month: A stroke had left me paralyzed on my right side. I woke up at Spaulding Rehab Center in Boston to signs plastered all around the building with their motto: “Find your strength.” Neuroplasticity made real.

During the course, our class had been reading the book The Brain that Changes Itself by Norman Doidge. Now this was no longer just hobby reading, but rather one possible map to my recovery.

In less than three years, my life has changed dramatically. But positive psychology remains a constant, even though my own circumstances have shifted. In fact, positive psychology became even more critical to me as I worked on a strategy to recover.

One of the first things that I recall about CiPP were Tal Ben-Shahar’s squiggly lines drawn on flipchart paper on the very first day of class, showing the possible course of how change takes place. Change seldom looks like a straight line moving from left to right and rising equally. More often than not, change looks like a random pattern of dots that could be a Rorschach test for the uninitiated.

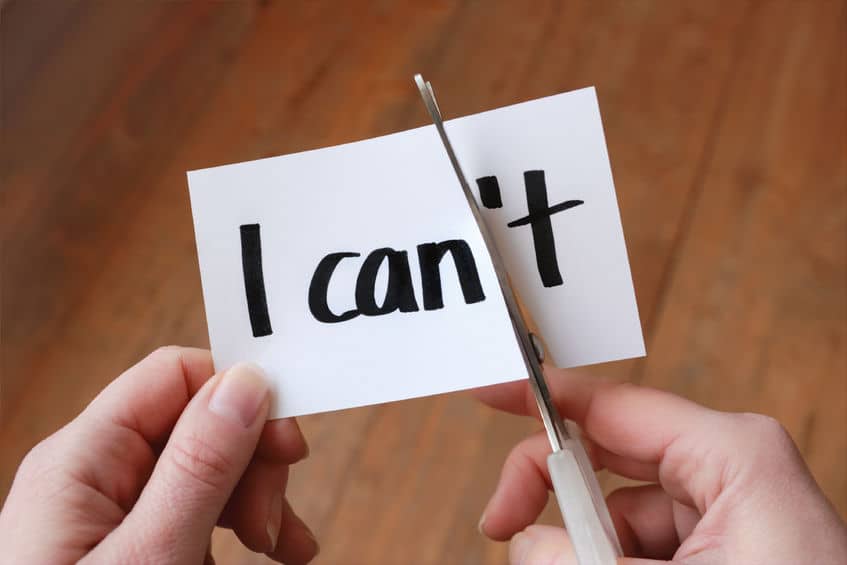

Change and the possibilities for change look stunningly different before and after a stroke. Before my stroke, I was trying to resolve the tension between self-acceptance and deep, lasting change. After the stroke, the tension remains the same, but the idea that I should be more accepting of my limits has changed, as therapists have tried to convince me to accept “my new life” and my “new limits.“ I’m not so sure yet that I want to embrace these limits. Who knows exactly where the limits are? What evidence is there that “dialing down” my recovery instinct is a good thing?

About 20 years ago, when my mother had a stroke, the idea of neuroplasticity had not yet taken hold among mainstream scientists. At that time, most scientists thought that regions of the brain were specifically designed for unique purposes. If you lost one part of the brain, you lost the abilities and skills that that part of the brain performed. As my neurologist said last year, “It used to be that scientists and medical professionals thought that any brain improvements needed to happen in the first year or they would never recover. Of course that’s when they stop measuring, after about a year.” Limits, it turns out, were imposed by the scientists themselves.

My original prognosis was dire: A medical resident told my wife that I might never communicate again. For nearly a year, I was unable to walk on my own. Then able to walk with the help of a cane. Then able to walk without a cane but without good balance. I currently cannot write (I am composing this on Siri). I don’t think I’d have been able to do any of this without what Carol Dweck calls a “growth mindset,” as opposed to a fixed one.

I had also underestimated the power of community and friendships to help buoy me up during my early recovery. One February evening during my stay at Spaulding Rehab, my father-in-law drove me to Somerville, Massachusetts—my first visit to my home city in six months. I was going to a fundraiser that was being held in my honor. Back in the hospital later that night, as I lay down in my bed, I was physically exhausted but emotionally and mentally energized by the experience. Grateful, with a full heart, are the only words I can use to describe how I felt.

We also learned about gratitude in CiPP. But I had not paid much attention to it. The heart, it turns out, plays a big role in recovery among patients and physicians. In his book Thanks: How the New Science Of Gratitude Can Make You Happier, Robert Emmons writes, “Grateful physicians are better physicians. Physicians who were trained to recognize their own emotions and emotions in others are going to be more effective healers. Studies have shown that emotionally intelligent physicians facilitate patient satisfaction and they themselves have higher satisfaction.”

Emmons continues, “A recent experiment found that grateful emotions led to better clinical problem solving in doctors. After having been given a small gift (a common procedure in mood induction research), internists made a more accurate diagnosis of liver disease in a hypothetical case than the doctors in the control group, who received no gift. Positive emotions such as gratitude lead to more efficient organization and integration of information, important cognitive tools and clinical assessment and diagnosis.”

I didn’t need science to tell me the benefits of gratitude. But it didn’t hurt. In fact, it felt really good.

One of the articles we read in CiPP was about Matthew Ricard, a scientist who became a Buddhist monk. Sometimes described as the “happiest man in the world,” Ricard defines happiness very differently: as a way of being that gives you more resources to deal with the ups and downs of life.

Scientists have studied how Ricard’s meditation sessions affect his brain. It turns out that the brains of people who meditate look very different than those who do not. It turns out that London taxi cab drivers have a very different brain map: the part of their brain dealing with spatial relations has become enlarged in response to their navigational focus. (This research was conducted by scientist Richard Davidson, at the request of the Dalai Lama.)

Positive psychology has kept me optimistic about the prospect of changing my brain. It has enabled me to keep a healthy balance in the tension between accepting and striving. Some health professionals have encouraged me to “dial it down”—to not expect too much.

According to Rabbi Bunim of P’shiskha, everyone should have two pockets, each containing a slip of paper. On one should be written: “I am but dust and ashes,” and on the other, “The world was created for me.” For me, the truth is found somewhere in between. But where?

This essay was originally published at kripalu.org.

Warren Goldstein-Gelb, CiPP2, is the publisher of B-Change.net, a podcast that talks with leaders and emerging leaders from the world of grassroots social change to strengthening skills in positive psychology. A graduate of the Department of Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning at Tufts University, Warren is the former executive director of the Welcome Project and now works part-time as a program director with the organization.

Wonderful to read this, Warren. So glad your recovery is going well and our positive psychology learnings have made a difference. Continued resilience and upward movement for you… rather than all those squiggles. I remember you fondly from CiPP2 (and lived in Boston area at the time). Cheers!